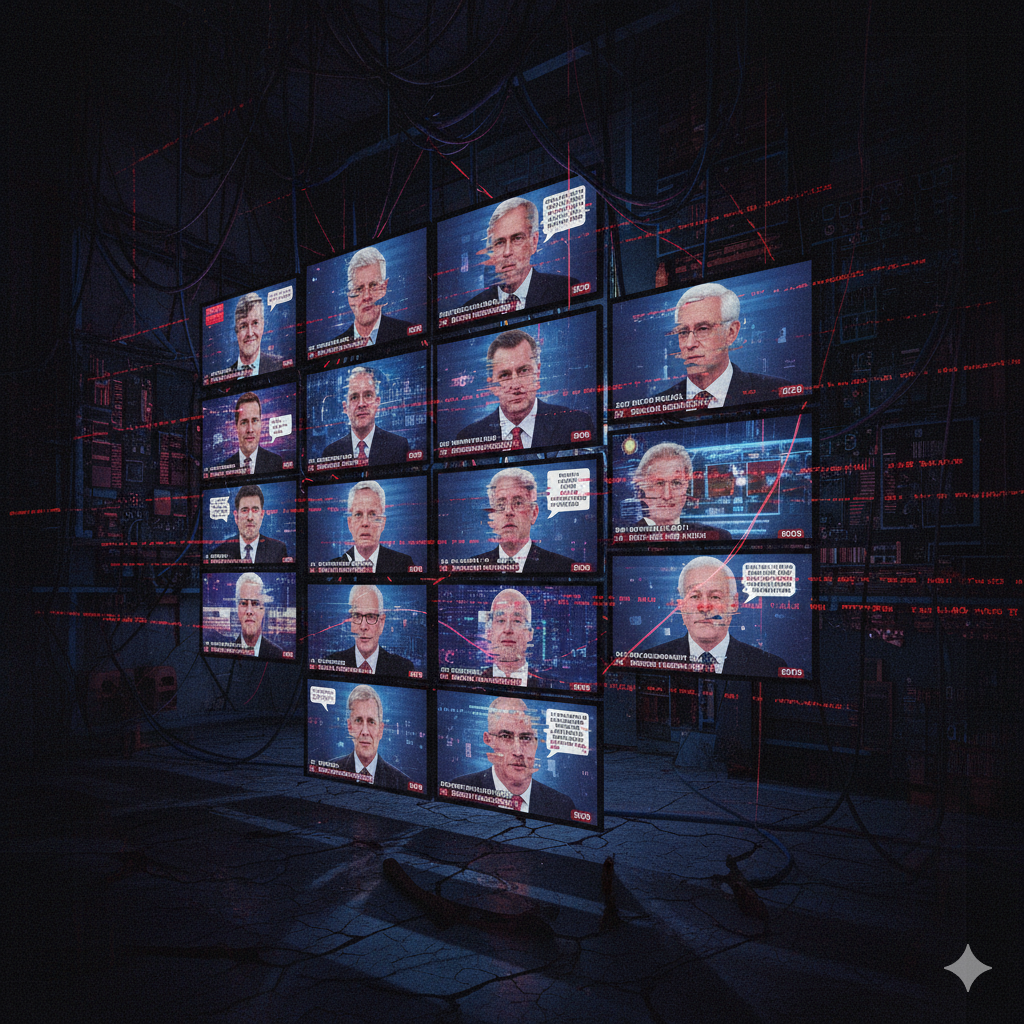

How to raise public awareness about the risks and opportunities of AI-manipulated information

Written by: Agita Pasaribu

TL;DR

High-quality deepfakes are hard for people to spot; accuracy often hovers near chance in realistic settings, and audio is especially difficult (Diel, 2024, Computers in Human Behavior Reports; Groh et al., 2022, PNAS).

Exposure is now common: in the UK, 43% of adults say they saw a deepfake in the past six months (Ofcom, July 2024).

Real-world incidents already affect elections (e.g., the Jan 2024 New Hampshire “Biden” robocall; Apr 2024 India campaign deepfakes), but impacts vary by context (FCC, 2024; Reuters, 2024).

Strongest evidence for countermeasures: prebunking/media-literacy and careful labeling/provenance, combined with platform enforcement and survivor-centered redress. Note: some interventions can unintentionally reduce belief in true information—design matters (systematic reviews and RCTs, 2022–2025).

Indonesia: 2024 was widely cited as the first election cycle where deepfakes surfaced locally; reporting channels exist (Kominfo).

Key takeaways

Humans struggle with high-quality fakes. A 2024 systematic review finds human deepfake detection varies widely and often falls near chance for realistic content; audio is hardest. Pairing people with tools helps (Diel, 2024; Groh et al., 2022).

Public exposure is mainstream. Ofcom (July 2024) reports 43% of UK adults encountered a deepfake in the prior six months (rising to 50% of 8–15-year-olds).

Election risks are real but contextual. Incidents in the US and India show misuse (e.g., Biden robocall; Bollywood-style candidate clips), yet case studies like Slovakia caution against overstating single-event effects (FCC, 2024; Reuters, 2024; HKS Misinformation Review, 2024).

Deepfake abuse is gendered. Cross-country surveys and legal analyses confirm women are disproportionately targeted by non-consensual synthetic intimate imagery (NSII) (Umbach et al., 2024; Kira, 2024).

Why this matters now

The years 2024–2025 make up a global “super-cycle” of elections, so the information environment people rely on to make civic choices is unusually consequential. Public exposure to synthetic and manipulated media is already mainstream.

In the United Kingdom, Ofcom found that 43% of adults reported seeing a deepfake in the preceding six months, with exposure among 8–15-year-olds reaching 50% (Ofcom, 2024).

In the United States, a widely publicized audio deepfake imitating President Biden urged voters to skip New Hampshire’s primary; by mid-year the Federal Communications Commission had moved toward multi-million-dollar penalties, signaling regulators’ growing willingness to act against deceptive synthetic media in electoral contexts (FCC, 2024). India, the world’s largest democracy, simultaneously grappled with viral, celebrity-fronted deepfakes during its April 2024 election, illustrating how culturally resonant personalities can become vectors for manipulation at scale (Reuters, 2024).

Indonesia and other countries in Southeast Asia have likewise seen increased discussion, reporting, and fact-checking around synthetic media during 2024 election periods, even as long-standing rumor ecosystems continue to shape online discourse. The important caveat is that deepfakes rarely act alone. As a case analysis of Slovakia’s 2023 vote argues, it is the interaction between deceptive content, platform dynamics, and pre-existing political vulnerabilities—not any single clip—that tends to influence outcomes (Harvard Kennedy School Misinformation Review, 2024)

What the latest evidence says

Start with the human factor. A 2024 systematic review of 56 studies finds that people, unaided, often struggle to spot polished deepfakes; accuracy trends toward a coin toss as quality rises, and audio fools more often than video (Diel, 2024). Experiments comparing people with top detectors show each notices different cues—together they do better—supporting “human-in-the-loop” verification instead of a single magic detector (Groh et al., 2022).

Harms are not evenly distributed. A ten-country survey (~16,000 people) documents both victimization (~2.2%) and perpetration (~1.8%) of non-consensual synthetic intimate imagery, with high reported harm and chilling effects on participation in public life (Umbach et al., 2024). Legal scholarship points to uneven protections and slow redress, leaving survivors exposed during the very window when viral harm compounds (Kira, 2024).

The prevention playbook is clearer than headlines suggest. Short prebunking videos that teach manipulation tactics—emotional language, false dilemmas, fake experts—work at platform scale (Roozenbeek et al., 2022). A 2024 meta-analysis shows media-literacy interventions reliably improve fake-news discernment across settings (Lu et al., 2024). Nudges can raise sharing standards, though effects vary by audience (Butler et al., 2024). A 2025 RCT finds both fact-checking and brief literacy training help—but in different ways—so layers beat silver bullets (Berger et al., 2025). Caution, though: one 2024 study warns that some widely cited prompts to “think harder” can also reduce belief in accurate news; evaluate interventions for side effects before scaling (Hoes et al., 2024).

Impacts across people, platforms, and policy

For people—and especially women and girls—the costs are intimate and immediate. Synthetic sexual images retraumatize, chill speech, and can derail careers; concerns about AI-generated CSAM add urgency and require distinct legal and operational responses (Umbach et al., 2024; European Parliament, 2025).

For platforms and newsrooms, design decisions are make-or-break. Clear, contextual labels (“Made with AI,” plus why that matters) can help users reason. Content provenance standards like C2PA/Content Credentials make authenticity visible across the creation chain. But provenance is one layer, not the whole shield: NIST’s 2024 roadmap endorses provenance and watermarking within a broader toolkit, and independent tests show current watermarks can sometimes be stripped or degraded—so redundancy matters (NIST, 2024; C2PA; ETH Zurich SRI, 2025).

For policymakers, the regulatory arc is heading toward transparency. The EU AI Act requires clear disclosure when people interact with AI systems and when media is AI-generated or significantly manipulated, including deepfakes (European Parliament, 2025). Voluntary “tech accords” launched in 2024 attempt cross-platform coordination against deceptive AI uses, recognizing that no single firm sees the whole threat surface (Munich Security Conference, 2024).

The 5-part playbook

1) Label what’s synthetic—and show your work.

Follow the EU AI Act model: when media is AI-generated or significantly altered, say so clearly, and tell people why it matters (context, not just a badge). Where possible, attach provenance (C2PA/Content Credentials) so authenticity can travel with the file. This aligns with NIST (2024), which recommends provenance, watermarking, and detection as a bundle—not silver bullets.

2) Prebunk before the spike.

Short, tactic-focused prebunking videos (think “how manipulation works,” not “this specific rumor”) improve resilience at scale, including on YouTube. Use them before debates, early voting, and high-risk news cycles; refresh periodically.

3) Enforce—fast—and build survivor-centred redress.

Platforms should resource trusted-flagger channels, prioritize rapid takedowns, and use hash-matching to prevent re-uploads, especially for NSII/CSAM. Regulators, for their part, can set expectations, as seen in recent UK guidance and the industry 2024 elections accord to fight deceptive AI content.

4) Invest in detection—people + machines.

Treat detection like cybersecurity: layered, monitored, and continually tested. Human–AI “co-pilots” catch more than either alone, and provenance signals give you something to verify against. (That’s also the logic behind the The Conversation piece’s call to invest domestically in detection capacity.)

5) Communicate against the liar’s dividend.

Now that everyone knows deepfakes exist, bad actors can deny real evidence. The fix is proactive authenticity: publish provenance for genuine content and avoid vague denials. The Brennan Center flagged this early in 2024; it remains a risk in every election.